19 Introduction

Machine learning represents a fundamental shift in how we approach problem-solving with computers. Rather than explicitly programming every rule and decision path, machine learning allows algorithms to discover patterns in data and make predictions or decisions based on these learned patterns. This approach has proven particularly powerful for complex problems where traditional rule-based programming becomes unwieldy or where the underlying patterns are too subtle for humans to easily codify.

At its core, machine learning is about generalization. We want to build models that can take what they’ve learned from historical data and apply that knowledge to new, previously unseen situations. This capability makes machine learning invaluable across diverse fields, from predicting stock prices and diagnosing diseases to recognizing speech and recommending movies.

Machine learning in biology is a really broad topic. Greener et al. (2022) present a nice overview of the different types of machine learning methods that are used in biology. Libbrecht and Noble (2015) also present an early review of machine learning in genetics and genomics.

19.1 Types of Machine Learning

The field of machine learning encompasses several distinct approaches, each suited to different types of problems and data structures. Understanding these categories helps practitioners choose appropriate methods and set realistic expectations for their projects.

Supervised learning forms the foundation of most practical machine learning applications. In supervised learning, we have access to both input features and the correct answers (labels or targets) for our training examples. The algorithm learns to map inputs to outputs by studying these example pairs. Classification problems, where we predict discrete categories, and regression problems, where we predict continuous numerical values, both fall under supervised learning. For instance, predicting whether an email is spam (classification) or forecasting house prices (regression) are classic supervised learning tasks.

Unsupervised learning tackles scenarios where we have input data but no predetermined correct answers. Instead of learning to predict specific outputs, unsupervised algorithms seek to discover hidden structures or patterns within the data itself. Clustering algorithms group similar data points together, while dimensionality reduction techniques identify the most important underlying factors that explain variation in the data. These methods often serve as exploratory tools, helping analysts understand their data better before applying supervised techniques.

Reinforcement learning takes a different approach entirely, focusing on learning through interaction with an environment. Rather than learning from fixed examples, reinforcement learning agents take actions and receive rewards or penalties, gradually improving their decision-making through trial and error. This approach has achieved remarkable success in game-playing scenarios and robotics, though it requires specialized techniques and considerable computational resources.

| Learning Type | Data Requirements | Goal | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised | Input-output pairs | Predict labels/values | Classification, regression |

| Unsupervised | Input data only | Discover patterns | Clustering, dimensionality reduction |

| Reinforcement | Environment interaction | Optimize decisions | Game playing, robotics |

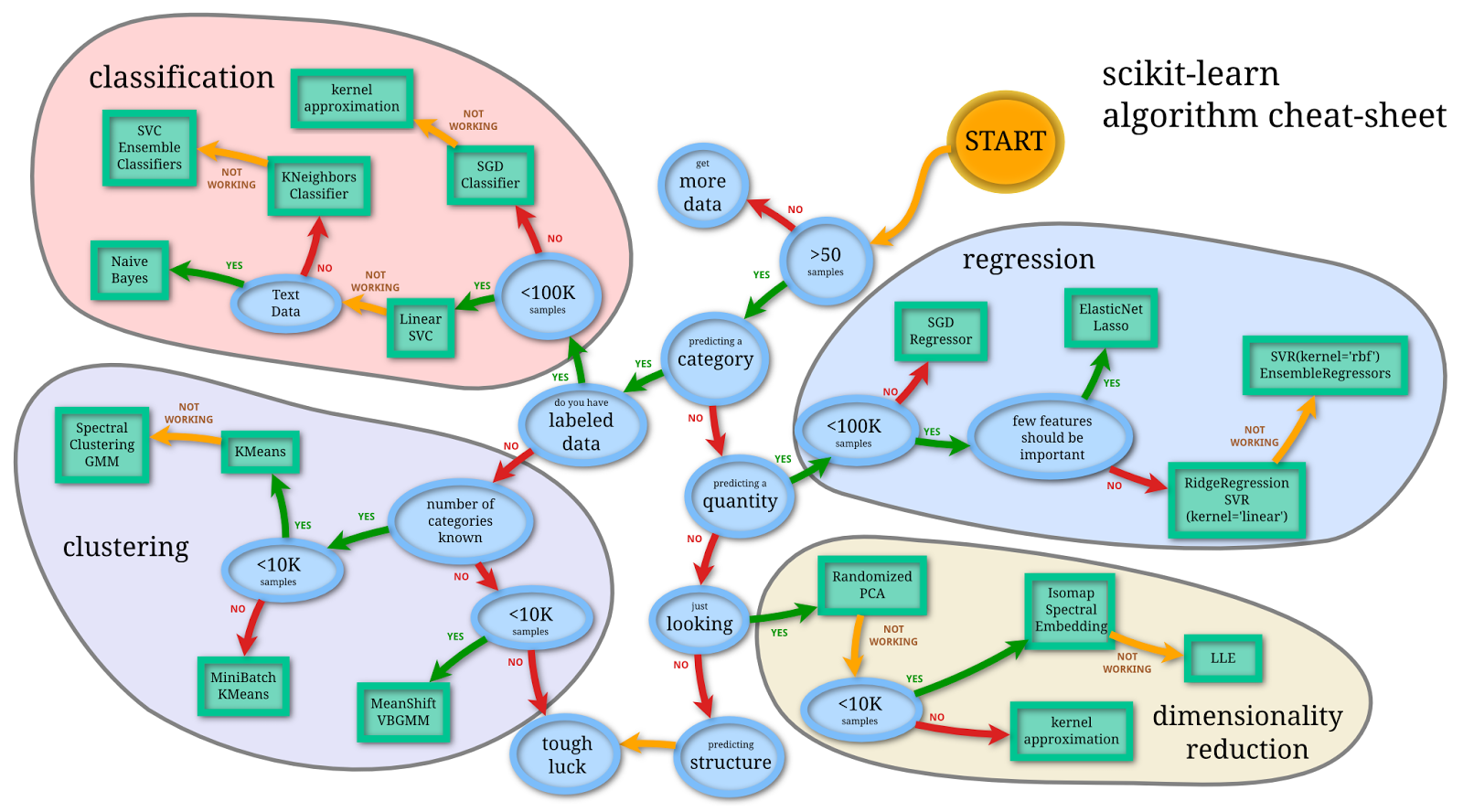

When thinking about machine learning, it can help to have a simple framework in mind. In Figure 19.1, we present a simple view of machine learning according to the scikit-learn package.

- Data

- Data is the foundation of machine learning and can be structured (tabular) or unstructured (text, images, audio). It is usually divided into training, validation, and testing sets for model development and evaluation.

- Features

- Features are the variables or attributes used to describe the data points. Feature engineering and selection are crucial steps in machine learning to improve model performance and interpretability.

- Models and Algorithms

- Models are mathematical representations of the relationship between features and the target variable(s). Algorithms are the methods used to train models, such as linear regression, decision trees, and neaural networks.

- Hyperparameters and Tuning

- Hyperparameters are adjustable parameters that control the learning process of an algorithm. Tuning involves finding the optimal set of hyperparameters to improve model performance.

- Evaluation Metrics

- Evaluation metrics quantify the performance of a model, such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score (for classification), and mean squared error, R-squared (for regression).

19.2 The Machine Learning Workflow

Successful machine learning projects follow a structured workflow that ensures robust, reliable results. This process begins long before any algorithms are trained and extends well beyond initial model development.

In a nutshell, the machine learning workflow consists of the following steps:

- Problem Definition: Clearly define the problem and determine if machine learning is the right approach.

- Data Collection and Preparation: Gather relevant data and preprocess it to make it suitable for modeling.

- Data Splitting: Divide the data into training, validation, and test sets to ensure unbiased evaluation.

- Model Selection: Choose the appropriate machine learning algorithm and configure its hyperparameters.

- Training: Fit the model to the training data, allowing it to learn patterns and relationships.

- Evaluation: Assess model performance using validation data and appropriate metrics.

- Deployment: Integrate the model into production systems for real-world use.

The journey starts with problem definition, where practitioners must clearly articulate what they’re trying to achieve and whether machine learning is the appropriate solution. Not every problem requires machine learning; sometimes simpler statistical methods or rule-based systems provide better solutions with less complexity and maintenance overhead.

Data collection and preparation typically consume the majority of time in real-world projects. Raw data rarely arrives in a format suitable for machine learning algorithms. Common preprocessing steps include handling missing values, encoding categorical variables, scaling numerical features, and addressing outliers. The quality of this preprocessing often determines the success or failure of the entire project.

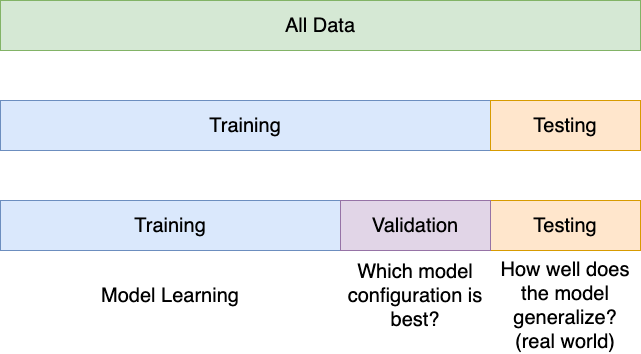

Data splitting deserves special attention because it directly impacts the reliability of your results. The training set teaches the algorithm, but if we evaluate performance on the same data used for training, we get an overly optimistic view of how well our model will perform on new data. This is analogous to letting students see exam questions while studying and then using the same questions for the actual exam.

One of the most crucial steps in the machine learning workflow is properly splitting your data into separate sets for training, validation, and testing. This separation serves as the foundation for honest evaluation and prevents overfitting.

- Training data is used to fit the model parameters.

- Validation data helps select the best model architecture and hyperparameters.

- Test data provides a final, unbiased estimate of model performance on new data.

The golden rule: never use test data for any decision-making during model development. Reserve it exclusively for final evaluation.

A common approach involves splitting data into 80% for training and 20% for testing. For more complex projects, a three-way split might use 60% for training, 20% for validation (model selection), and 20% for final testing. Cross-validation provides an alternative approach where the training data is repeatedly split into smaller training and validation sets, providing more robust estimates of model performance while still preserving an untouched test set.

k in k-nearest-neighbor) as well as model parameters (like betas in linear regression), a separate validation set is essential.

Model selection involves choosing both the type of algorithm and its specific configuration. Different algorithms make different assumptions about the data and excel in different scenarios. Linear models work well when relationships are approximately linear and interpretability is important. Tree-based methods handle nonlinear relationships and interactions naturally but may overfit with limited data. Neural networks can model complex patterns but require large datasets and careful tuning. Hyperparameters are the parameters that describe the details of the model such as the depth of a decision tree, the choice of k in k-nearest neighbors, or the learning rate in gradient descent. Hyperparameter tuning is the process of finding the best values for these parameters, often using techniques like grid search or random search combined with cross-validation.

Training is where the algorithm actually learns from the data. During this phase, the model adjusts its internal parameters to minimize prediction errors on the training set. However, the goal isn’t to achieve perfect performance on training data. Models that fit training data too closely often fail to generalize to new examples, a problem known as overfitting.

Evaluation determines whether our model is ready for deployment. This involves multiple metrics beyond simple accuracy, including precision, recall, F1-score for classification, or mean squared error and R-squared for regression. We also examine model behavior across different subgroups in our data to ensure fair and consistent performance.

19.3 Understanding Overfitting and Underfitting

Recall that the goal of machine learning is to build models that generalize well to new, unseen data. Any model that is complex enough can perfectly model data given to it. However, achieving this balance between fitting the training data and maintaining good performance on new examples (ie., generalization) is the goal, not just performing well on the training data.

The concept of overfitting represents one of the central challenges in machine learning. When a model overfits, it learns the training data too well, memorizing specific examples rather than generalizing patterns. This results in excellent performance on training data but poor performance on new, unseen data.

Imagine teaching someone to recognize cats by showing them 100 photos. An overfitted learner might memorize every pixel of those specific photos rather than learning general features like whiskers, pointed ears, and fur patterns. When shown new cat photos, they would struggle because they focused on irrelevant details specific to the training images.

Underfitting represents the opposite problem. An underfitted model is too simple to capture the underlying patterns in the data. It performs poorly on both training and test data because it lacks the complexity needed to model the relationships present in the data. Continuing our cat recognition analogy, an underfitted model might only look at image brightness and miss all the important visual features that distinguish cats from other animals.

Code

set.seed(123)

sinsim <- function(n,sd=0.1) {

x <- seq(0,1,length.out=n)

y <- sin(2*pi*x) + rnorm(n,0,sd)

return(data.frame(x=x,y=y))

}

dat <- sinsim(100,0.25)

library(ggplot2)

library(patchwork)

p_base <- ggplot(dat,aes(x=x,y=y)) +

geom_point(alpha=0.7) +

theme_bw()

p_lm <- p_base +

geom_smooth(method="lm", se=FALSE, alpha=0.6, formula = y ~ x)

p_lmsin <- p_base +

geom_smooth(method="lm",formula=y~sin(2*pi*x), se=FALSE, alpha=0.6)

p_loess_wide <- p_base +

geom_smooth(method="loess",span=0.5, se=FALSE, alpha=0.6, formula = y ~ x)

p_loess_narrow <- p_base +

geom_smooth(method="loess",span=0.05, se=FALSE, alpha=0.6, formula = y ~ x)

p_lm + p_lmsin + p_loess_wide + p_loess_narrow + plot_layout(ncol=2) +

plot_annotation(tag_levels = 'A') &

theme(plot.tag = element_text(size = 8))Warning in simpleLoess(y, x, w, span, degree = degree, parametric = parametric,

: k-d tree limited by memory. ncmax= 200Warning in sqrt(sum.squares/one.delta): NaNs produced

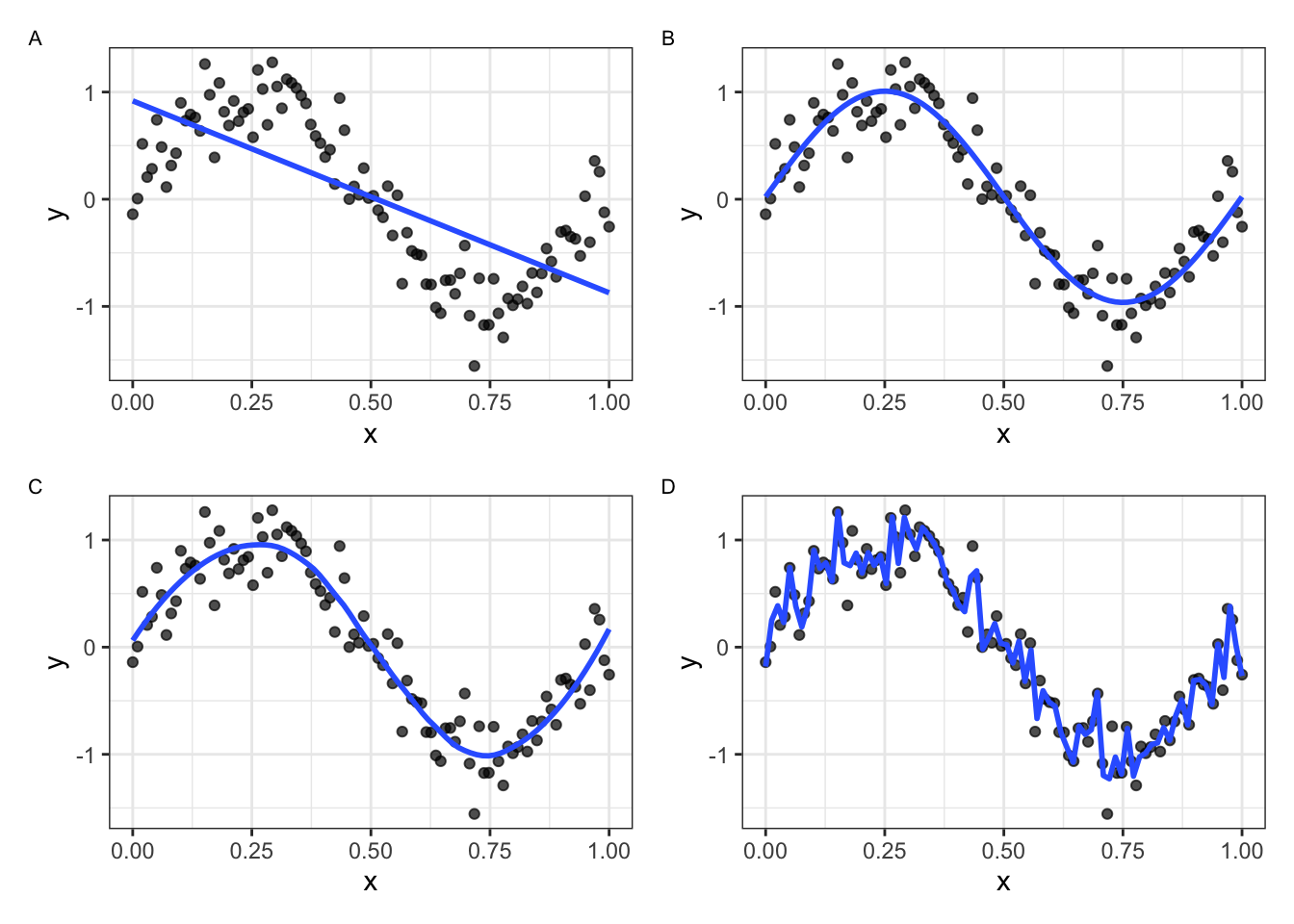

In Figure 19.3, we simulate data according to the function \(f(x) = sin(2 \pi x) + N(0,0.25)\) and fit four different models. Choosing a model that is too simple (A) will result in underfitting the data, while choosing a model that is too complex (D) will result in overfitting the data. For model (D), the loess model with a narrow span, the fitted line follows the noise in the data too closely, capturing random fluctuations rather than the underlying trend. In contrast, models (B) and (C) demonstrate good fits, capturing the essential pattern without being overly complex.

The relationship between model complexity and performance often follows a characteristic U-shaped curve. Very simple models underperform due to underfitting. As complexity increases, performance improves as the model captures more relevant patterns. However, beyond an optimal point, additional complexity leads to overfitting and degraded performance on new data.

Overfitting reveals itself through a growing gap between training and validation performance. If your model achieves 95% accuracy on training data but only 70% on validation data, you’re likely overfitting.

Monitor both training and validation metrics throughout model development. The best models show similar performance on both sets, indicating good generalization.

Several strategies help combat overfitting. Regularization techniques add penalties for model complexity, encouraging simpler solutions. Cross-validation provides more robust estimates of model performance by training and validating on multiple data splits. Early stopping halts training when validation performance begins to degrade, even if training performance continues improving. Feature selection reduces the number of input variables, focusing the model on the most relevant information.

The bias-variance tradeoff provides a theoretical framework for understanding these phenomena. Bias refers to systematic errors due to overly simple models, while variance refers to sensitivity to small changes in training data. High-bias models underfit, while high-variance models overfit. The optimal model balances these competing sources of error.

19.4 Cross-Validation and Model Selection

Cross-validation addresses a fundamental challenge in machine learning: how do we reliably estimate model performance when we have limited data? Simple train-test splits can be misleading, especially with small datasets, because performance estimates depend heavily on which specific examples end up in each set.

K-fold cross-validation provides a more robust solution. The training data is divided into k equal-sized subsets (folds). The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. This process yields k performance estimates, which can be averaged to get a more stable assessment of model quality.

Five-fold and ten-fold cross-validation are common choices, providing good balance between computational efficiency and reliable estimates. Leave-one-out cross-validation represents an extreme case where k equals the number of training examples. While this maximizes the use of training data, it can be computationally expensive and may provide overly optimistic estimates for some types of models.

Stratified cross-validation ensures that each fold maintains the same proportion of examples from each class, which is particularly important for classification problems with imbalanced datasets. Time series data requires special consideration, as temporal order matters. Time series cross-validation uses only past data to predict future values, respecting the temporal structure.

Cross-validation serves multiple purposes in the model development process. It helps select the best algorithm from a set of candidates, tune hyperparameters within a chosen algorithm, and provide realistic estimates of expected performance on new data. However, it’s crucial to remember that cross-validation results still come from the training data. Final model evaluation should always use a completely separate test set.